For about a year or more I’ve been interested in the relationship (or potential lack thereof) between autism and schizophrenia. As is commonly known, autism and epilepsy share considerable comorbidity and probable etiology with one another. Interestingly, back around the middle of the 20th century some psychiatrists believed that epilepsy provided a protective factor against the development of schizophrenia, which suggests that, if true, autism could also share a similar relationship with schizophrenia [1]. There are certainly cases to the contrary, e.g., Phelan-McDermid Syndrome; rates of schizophrenia appear to be higher in families with autism [2]; and there’s modest overlap of genetic risk factors. However, a recent study by Taylor et al. (2015) suggests that autism may share little overlap with the positive symptoms of schizophrenia which are so characteristic of the classic form.

The team performed a longitudinal study on 5,000 twin pairs, of which 32 were concordant for a diagnosis of autism according to the AQ and ADOS. Twins were assessed at ages 8, 12, 14, and 16. Psychotic experiences were assessed using the Specific Psychotic Experiences Questionnaire (SPEQ), which included items covering positive symptoms of schizophrenia (paranoia, hallucinations, grandiosity, and cognitive disorganization), and negative symptoms (avolition, social interaction, affective experiences and responses, and altered motor movements including speech). Some items in the latter category were removed due to considerable overlap with autism criteria.

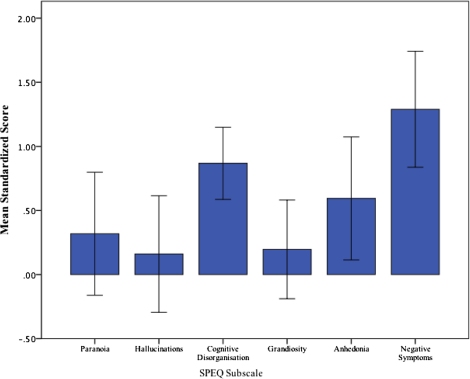

Taylor et al. (2015) found that negative symptoms were most strongly expressed in the autism group compared to controls, including symptoms of anhedonia (inability to feel pleasure). In addition, there was significant overlap in expression between autism and cognitive disorganization. However, the team found that differences between groups in expression of paranoia, hallucinations, and grandiosity were insignificant. This was in spite of the fact that mean AQ scores were largely identical regardless of whether a first-degree relative was diagnosed with a psychotic disorder or not.

Figure #2 from Taylor et al. (2015), showing mean scores on SPEQ subscores.

So, schizophrenia and autism seem to simultaneously share much in common and yet infrequently occur together. Is that because autism, as was proposed about epilepsy by de Meduna in 1936, precludes the development of schizophrenia? That’s a question that continues to rumble around my brain.